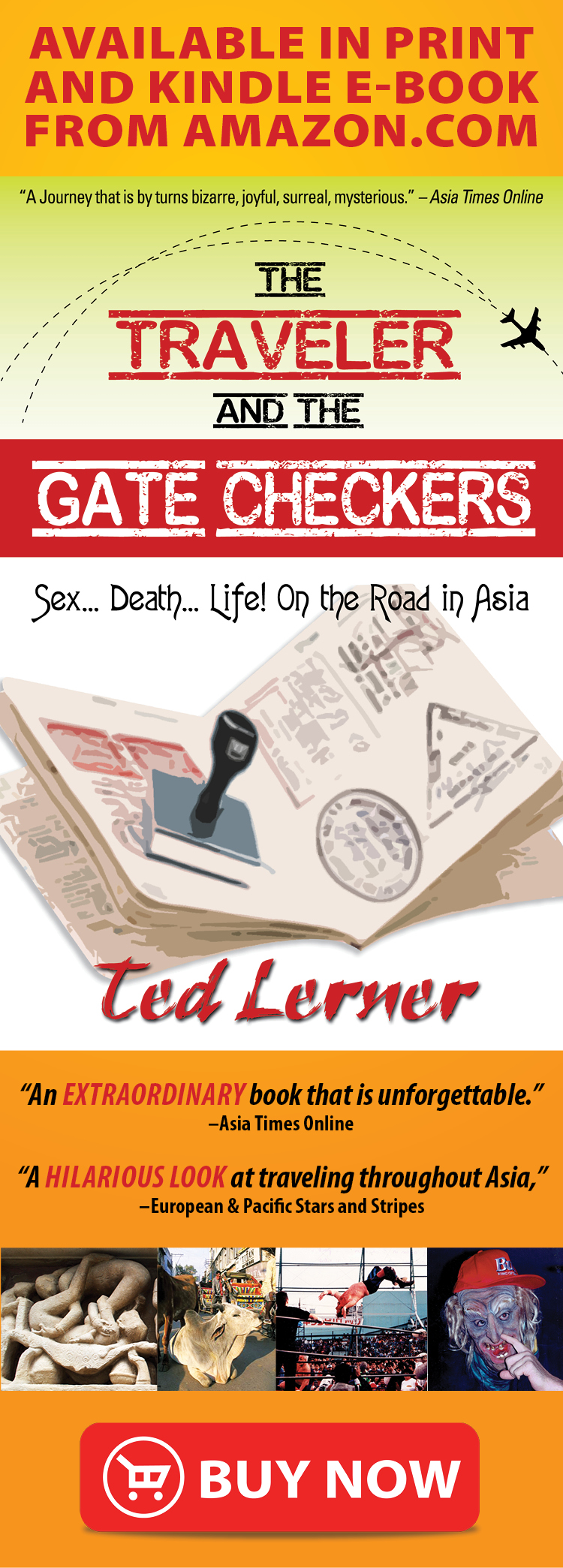

Breast Is Best At Fabella Memorial Hospital

The Fabella Memorial Hospital maternity ward in Manila is packed wall to wall with mother’s breas feeding their babies. (Photo Courtesy Manila Bulletin)

*This story appeared in Manila’s Businessworld Newspaper in the early 2000’s. It’s both heartwarming and a mind blower at the same time.

By Ted Lerner

The walk leading up to the JoseFabella MemorialHospital can certainly be an eye popping one. As you approach the hospital, located in a teeming, semi-rundown neighborhood in the Santa Cruz section in the heart of old Manila, you pass dilapidated shacks, beer houses, decrepit bus terminals, sidewalks crowded with vendors selling cheap clothes and toys from China, ramshackle canteens, overcrowded auto shops doing work right on the street and hordes of grimy, barefooted kids playing basketball on makeshift hoops.

But for sure it’s not just the surroundings which make one shake his head in disbelief. There’s also the numbers associated with this, the Philippines and one of Asia’s largest maternity hospitals; more than 36,000 births per year, over 4000 ceasarian sections, 5000 major surgeries, more than 76,000 inpatient admissions and over 100,000 consultations.

Things become even more incredible when you realize that the 700 bed Fabella is the maternity hospital for the poorest of Manila’s poor, it’s a government run hospital and, of all things, it’s services are free. Surely Fabella has all the trappings of a third world nightmare scenario in medicine and health care.

And yet when you first walk in to the lobby of this 78 year old institution, ominously located in an old prison, everything one sees begins to tell a much different story. Notably there are the walls, which are covered with glowing accolades and photos of international dignitaries who have visited Fabella over the years. There are messages from Unicef and the World Health Organization, recognizing Fabella for being a “Baby friendly” hospital. Queen Sophia of Spain came to marvel at the goings on here, as did former US First Lady Hillary Clinton. Another picture shows former Philippine president Corazon Aquino handing out an award. A nearby photo shows medical professionals from Africa and China posing in front of the hospital.

So how does a government run hospital, sitting amidst the teeming and overcrowded urban landscape of Manila, in this era of crisis and cutbacks, become a model maternity hospital recognized by the UN and WHO and one that is regularly visited by dignitaries and health care professionals marveling at the happenings?

Amazingly the answer is as simple and as time honored as giving birth itself. For 61 year old Dr. Ricardo Gonzales, Fabella’s director and the driving force behind it’s phenomenal success, the answer comes down to the breast, or as he likes to say in his almost mantra like fashion, “Breast is best.”

Yes, mother’s milk, which is filled with infection fighting nutrients and immune building capabilities, is absolutely free and has benefits that can affect an entire hospital operation. But there is more to this success, as well. It’s also ingenuity borne out of economic necessity and a boundless enthusiasm. Dr. Gonzales and his staff have managed to buck the awesome odds and create a hospital where the chances of a baby’s survival are as good as if not better than hospitals in affluent areas.

When Dr. Gonzales came to Fabella in 1987, however, it was hardly the ideal place to have ones baby. The hospital was run down, offered substandard service, had low morale among its employees. It was overcrowded and was barely paying its bills. In other words a typical government run hospital in a cash strapped third world country.

“When I came in 1987,” said Dr. Gonzales, “there was already a department order encouraging all government hospitals to practice rooming in(the practice of having the baby stay with its mother from the time of its birth) but there was only token compliance.” Breast feeding was not encouraged either. Like at most other hospitals, babies at Fabella were separated from their mothers and put in a nursery, where they were fed infant formula milk according to a schedule. Since it catered to the poorest of the poor, the mothers who came to Fabella were often undernourished and easily contracted infections, which were often passed on to their newborns, who then could pass on the infections to other babies in the nursery. Dr. Gonzales inherited a system that was, in his mind, everything that birth shouldn’t be.

“It’s the medicalization of giving birth,” he said. “The western way is to believe that giving birth is some kind of illness, that technology is always best.” It’s a way, he points out, that seems to support mainly the drug companies, the insurance companies and the medical equipment companies. Incredibly the mothers, he notes, seemed to be left out of the picture.

Dr. Gonzales, however, didn’t start out on any particular crusade. He was taught the western ways of medicine during his schooling and admits to not having questioned them much. He saw the problem at Fabella as a technical and a managerial one; how to offer the best care for the mothers and their babies for as little as possible. He found his answer not through technology, but by turning back the clock and returning to the basics.

But implementing such drastic change in policy was another story, especially when the “westernized” way of doing things was so widely accepted. Imbued with a zeal to put mothers and their babies first, and fueled by economic necessity, Dr. Gonzales hit the ground running. He traveled to San Diego, California with his chief nurse and three of his staff, to undergo training in a lactation management course. They then proceeded to San Jose to observe a milk-bank program there.

Upon return to the Philippines, Dr. Gonzales and his staff were 100 percent sold on breast feeding. Employing his simple and folksy mantra “breast is best,” he immediately introduced a mandatory breast feeding and rooming-in policy, closed down the nursery and banned all infant milk formula and bottles. This meant that for the duration of her stay in the hospital, a new mother had her baby beside her to nurse whenever and as often as the baby needed.

Many of his staff of 300 were reluctant to accept these new changes, believing the infants would be subject to more infections. But the opposite proved true. Infection rates went down and the staff was won over.

The benefits snowballed from there. With infection rates down, this meant the women recovered earlier, which meant less congestion. By closing the nursery and banning infant formulas and bottles, Fabella saved over $250,000 in annual expenses. This allowed the hospital to pour the money back in to vital services for the mothers and their babies; new operating rooms, gynecological services and treatment for women with cancer, pre-natal services and pediatric care. The savings also allowed administrators to introduce services that complimented its rooming-in and breast feeding policies. Babies born with cleft palates, for example, are immediately fitted with a dental plate made right in the hospital. The plate allows the baby to form a vacuum with its mouth so it can successfully suckle.

Another obstacle Dr. Gonzales faced was that some doctors and nurses, while aware of the benefits of breast feeding, believed that many mothers simply can’t produce milk. They didn’t believe that Dr. Gonzales could enforce his strict policy of requiring mothers to breast feed before they can be discharged. Market forces and cultural stigmas seemed to be at play. Parents are bombarded with advertisements that suggest that formulas will lead to smarter, healthier children. Ignorance has led some mothers to believe they can’t breast feed because their breasts are too small or it’s shameful. And so they spend their meager income on expensive milk, often times preparing it with dirty water which can cause diarrhea or scrimping on the powder which leads to malnourished babies. It’s a viscous and dangerous cycle.

But again, Dr. Gonzales was not swayed. His “breast is best”policy starts the minute the baby is born. One of his innovations is called “latching on,” where a new born baby, still wet with fluids, is put to the mother’s breast right on the delivery table. The baby receives his first immunization with his mother’s first milk, a yellowish fluid called colostrum, which is rich in nutrients and immunoglobins and protects the baby against infections. This initial suckling also has another benefit; it helps stimulate the uterus to contract and expel the placenta without the use of expensive drugs.

Dr. Gonzales also employs a “lactation brigade,” a group of women volunteers, who roam the crowded wards and help new and reluctant mothers to begin expressing milk. For those babies born prematurely, the hospital employs a milk bank. Premature babies are fed mother’s milk through a tube or by a small glass until such time the baby can properly breast feed. Another innovation which evolved out of cost cutting measures helped as well. By pushing two beds together the hospital could accommodate more women by having them lay cross wise on the bed. This also allowed first time mothers to be placed side by side with second and third time mothers so the new mothers would receive encouragement and tips.

There were still other benefits from breast feeding as well. Fabella used to have a problem with new mothers simply leaving the hospital after giving birth and abandoning their babies. This left Fabella with the task of placing the child with an orphanage. But it seems breast feeding has done more than made healthier babies. It also develops a special bond between mother and child. Since the new policy was implemented, cases of abandonment have gone from over a dozen in one year, to almost zero.

One of the more fascinating aspects of Fabella is that considering the incredible amount of births that happen on a daily basis, the place is extremely quiet. At Fabella babies enter the world sans the bells and whistles, the cheering husband, the wild family celebrations. This is not the same birth that takes place in an upscale western-type hospital.

There are no Lamaze classes at Fabella and certainly no coaching husbands in the delivery room. The reality of a cash strapped hospital which delivers sometimes over 100 babies a day means that the family is excluded. Strict control must be maintained as in such a crowded environment infections can spread easily. Husbands and family members are relegated to the outside grounds of the hospital, where they curl up on wooden benches and wait for word from inside the hospital. The sheer numbers dictate that it be this way. One family member is allowed to come to a desk in the new mother’s ward and visit the mother for only a few minutes. Then they must leave the hospital.

Another manifestation of the crunch Fabella confronts daily is the various women pacing back and forth outside the hospital waiting to go in to labor. Because of the severe limitations on bed space, a woman can only check in when she’s gone in to labor. Some women are giving birth for the first time and they don’t know what’s happening, so they show up three days too early. Some are only hours away. At anytime you can see dozens of women pacing back and forth rubbing their big bellies trying to spur the baby to come out.

And yet even outside the hospital Dr. Gonzalez has tried to do something for the expectant mothers. He took an unused corner of the hospital near the admitting section and turned it into a miniature version of a native style Filipino house, complete with latice windows, a balcony and bed inside for the women to relax on while they wait to go in to labor.

Once labor has begun, the women are checked in and everything becomes no-nonsense. They are asked to donate blood for the blood bank. They change in to hospital provided gowns and are wheeled upstairs to the delivery room. The delivery room resembles a large industrial kitchen; brightly lit, with white tiled floors and walls. There are no partitions. The women are lined up one after the next. In this particular case 12 women, some just about to deliver, others who had just given birth lay on gurneys. There is not enough staff to comfort the women as the doctors and nurses are simply too busy. On the average they are handling four new births an hour. Interestingly the room is quiet, without any of the screaming or cursing that one normally associates with women giving birth. One nurse pointed out that this form of communal birth works as a form of control for the women, as if seeing first hand that you’re not alone helps the women to calm down.

After the birth the babies are immediately placed to the mother’s breast. The baby is then washed, wrapped in a cloth and placed between its mother’s legs. The hall outside the delivery room is filled with new mothers laying on gurneys, their new born babies only minutes old, placed right between their legs.

Quietness seems to be the norm at Fabella. Down the hall the new mother’s ward is filled to capacity with over 100 women in white gowns and their new babies. The sultry air is broken only by several ceiling fans and standing fans. A room full of women giving birth is hardly flattering. The women all look dazed, out of it, tired. They move slowly, if at all. Some breast feed their babies, others sleep.

Most of these women will check out 24 hours after giving birth. Each one will have initiated breast feeding. Incredibly the services and medicines at Fabella are entirely free. Before she leaves, each new mother will receive a visit from a social worker. The social worker will inform the mother how much was spent on her birth. The social worker will then ask the mother if she liked the services at Fabella and if she did, she will be asked if she would like to make a donation. In nearly every case, the woman or her family, no matter how poor, gives money. It could be ten dollars or perhaps $40. One nurse mentioned a case of a father who didn’t have any money but came back two years later and gave the hospital $50.

The idea of the hospital being “free” of charge is another innovation of Dr. Gonzales. When the services are free, he says, then the patient and their families don’t have anything to worry about. He wants not only the mothers to feel comfortable but the families as well. If the family knew they had to buy medicines they might be ashamed if they had no money. Thus they wouldn’t come. They might just stay at home and deliver the baby there.

Clearly Dr. Gonzales and his staff have created at Fabella more than a well run hospital. They have created a sort of city of refuge, a place where even the lowest, poorest woman can come in her most dire time of need and, without question or comment, receive not only proper care and treatment, but also dignity and respect. Considering its location and the circumstances the hospital operates under, some people might call what goes on at Fabella Memorial a miracle. Dr. Gonzales would probably call it good old fashioned practicality. Either way, something special is obviously happening amidst the urban squalor that is Manila.