Back From The Brink And On To The Streets

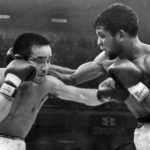

Former boxer Alvin Felisilda, right, poses with his new motorcycle which will be converted to a passenger tricycle, and will allow him to earn a living after a life threatening ring injury ended his career. Also in the picture is boxing referee Bruce McTavish, left, and Felisilda’s manager, Leonel Lazarito.

*This article originally appeared in the Ring Magazine

By Ted Lerner

“Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach him how to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”

Lao Tzu, sixth century B.C. Chinese philosopher

Standing inside the small, air conditioned showroom of a Yamaha dealership in the southern Philippine town of Cagayan de Oro city, Alvin Felisilda is hardly thinking about ancient Chinese philosophy. Instead, the 23 year old quietly eyes his future–a shiny, brand new motorcycle that will soon have his name on it. At a table off to the side, the store manager, along with New Zealand boxing referee and long time Philippine resident Bruce McTavish, sort out the business, counting the money, organizing the paperwork.

Of course, this isn’t what Felisilda had dreamt of when he began boxing at 16 years old. Boxing was going to lead him and his large family out of crushing poverty and to some real money. Boxing would help him achieve his dream of becoming a world champion like his hero, Gerry Penalosa. Actually, despite a rough start, he had made progress, eventually winning the Philippine bantamweight title. Then, however, in November, 2003, it all went terribly wrong, when Felisilda nearly died from a serious brain injury suffered in a fierce OPBF title match in Kobe, Japan.

But now, standing in the Yamaha dealership waiting for his chance to affix his signature to the paperwork, it is obvious by his quiet nervousness, the flicker in his eyes, that Felisilda knows he is blessed–by circumstances, by luck, by the fact that there are some people in boxing who do care about a fighter even when he’s down and out. And he can see clearly that he is about to reclaim some of his life, or at least get a chance at it. That’s all you can ask for after nearly dying. Just simple things. Just a chance. And that motorcycle is that chance.

Chances are few in the village of Malugan, a small farming community in the southern Philippine province of Misamis Oriental, Mindanao, where extreme poverty stalks the landscape. Felisilda’s father ekes out a living as a tenant farmer growing corn, while his mother takes care of the brood of nine children. The family is crammed into a simple, three room house, with no electricity and no running water.

In some ways Felisilda’s story mirrors Mindanao’s most famous boxer, Manny Pacquiao, who grew up three hours drive away in General Santos City. Like Pacquiao, Felisilda dropped out of school in the sixth grade and soon found work in a local bakery. It just so happened that the owner of the bakery had a small boxing stable, where Felisilda developed a liking to the sport. When he was 16 years old, Felisilda eventually found his way to the stable of one of Mindanao’s largest managers and promoters, Leonil Lazarito, a local businessman and farmer who lives three hours away in the rural farming community of Bukidnon.

By any standards in professional boxing, Lazarito could be considered a saint of a man. He started managing fighters in 1988, and his stable has at times numbered over 50 young men. Lazarito takes in any kid who comes knocking on his door, houses them, feeds them three meals a day, trains them, tries to find them fights and even helps them to find work should they decide to leave the sport. Without exception all the kids are desperately poor. Sometimes it’s the kids’ parents who come to him, pleading with Lazarito to take their son and turn him into a boxer, because they don’t know any other way out of the grinding, persistent poverty.

“Whoever knocks on my door, I accept,” Lazarito says“I do it for the love of boxing. But I always explain to them that the sport is brutal. They say they don’t care. They have no choice.” Although Lazarito has seen streams of fighters pass before his eyes, he noticed a little something special in the youngster from Malugan.

“I knew that if Alvin will be developed, he can become a champion,” he said. “He had a strong punch. He was one of my best boxers.”

“I dreamt of being a champion,” Felisilda said, naming former WBC superflyweight champion Gerry Penalosa as one of his idols. “I wanted to emulate the Philippine Champions. I wanted to make money.”

As is typical in the poorer parts of Asia, he was moved quickly, and often fought abroad under impossible conditions. Not surprisingly, the defeats mounted. In only his fourth fight he fought a ten rounder in Thailand, losing a points decision. Two fights later he went the distance and lost against current WBC flyweight champion Pongsaklek Wonjongkam. Then, in his 14th fight, with a record of 4-8, but obviously battle hardened, he won the Philippine Bantamweight title via convincing knockout. Nobody back in Malugan even saw the fight, because nobody had a television. But people in the nearby bigger town of El Salvador saw the fight on TV and relayed the news to Felicilda’s family. It was the biggest thing anyone in that area had ever accomplished and Felisilda became an instant hero.

Exactly three months later, in November, 2003, Felicilda traveled to Kobe, Japan to challenge current WBC bantamweight champ Hozumi Hasegawa for the OPBF bantamweight championship. Felisilda went down once in the third, then again in the fifth. Lazarito, who was in the corner, says that although the fight was fairly one sided, he didn’t notice anything particularly wrong with his ward. But after Felisilda absorbed some heavy blows in the eighth and ninth rounds, Lazarita decided it wasn’t worth continuing and stopped it in the corner before the start of the tenth.

For two minutes Felisilda paced around in the ring awaiting the official decision. He says now he never felt anything overtly wrong. But suddenly he slumped over and collapsed. Japanese boxing officials rushed Felisilda to the hospital, where within minutes of examining him, doctors decided they had to operate. Felicilda’s brain was swelling fast, they said, and if they didn’t open up the skull to relieve the pressure, the youngster from Mindanao was in danger of dying right then and there.

Working quickly, doctors proceeded to remove a portion of the left side of Felicilda’s skull, a round piece the size of a drink coaster and about a half an inch thick. Fortunately the operation went well.

“Right after the surgery, the doctor told me he’d be ok,” Lazarito said. Felicilda woke up three days later. “I asked him questions. ‘What’s my name? What’s your name?’ Right there I knew he was able to maintain his short term and long term memory.”

Back home in Malugan, the family heard by portable radio that a Filipino boxer fighting in Japan had been injured in a fight and was now in a Japanese hospital fighting for his life. Cut off from the outside world because of their location and poverty, all they could do was pray.

Despite the successful surgery, Felicilda was not out of danger yet. He had to remain in the hospital for a total of 45 days, most of it with his hands tied, lest he accidentally touched the gap in his skull. Then there was the question of who would cover the hefty expenses.

Japanese boxing officials took care of all the bills for the initial operation. But the hospital needed an additional $15,000 to close the hole in Felicilda’s skull with a synthetic covering, followed by a skin graft. Lazarito, who had brought many fighters to Japan before and had lots of contacts, made some calls and within a day was able to come up with the money.

When Felisilda returned to the Philippines he immediately headed south to visit his family. Overjoyed, the family threw a big party, and even roasted a pig. But getting home in one piece was just the first hurdle.

“Alvin needed guidance,” Lazarito said. “He couldn’t do manual jobs. He can’t carry heavy things.” The Philippine government doesn’t have a fund for down and out boxers and without an education, and the inability to do manual labor, Felisilda’s future looked bleak at best. Enter again Lazarito.

Lazarito contacted the OPBF president, Frank Quill, in Australia, to ask for assistance. Quill, through McTavish, opened up a bank account for Felisilda and allowed him to withdraw $100 a month through an ATM card. Felisilda used the monthly stipend to buy food, visit a psychiatrist, and even help out his sister, who asked for some funds to travel abroad for work.

After regaining his strength, Felicilda started using some of the money to rent a tricycle cab and try his luck on the streets of the regional capital, Cagayan de Oro. Tricycles, which are basically motorcycles with a passenger cab welded onto its frame, are cheap and common forms of transportation throughout the Philippines. In Cagayan de Oro, a tricycle driver earns just 10 cents a passenger, per kilometer. It’s a job which provides subsistence living, perhaps a little more if the driver is lucky.

Lazarito, who to this day still keeps the circular piece of Felisilda’s skull as a memento, monitored Felisilda to make sure riding a motorcycle all day didn’t harm him. Although he was able handle the rigors of plying the busy city streets, the economics of the job didn’t add up. Felisilda had to rent the tricycle for $4 a day. At most he grossed $6 and pocketed just two.

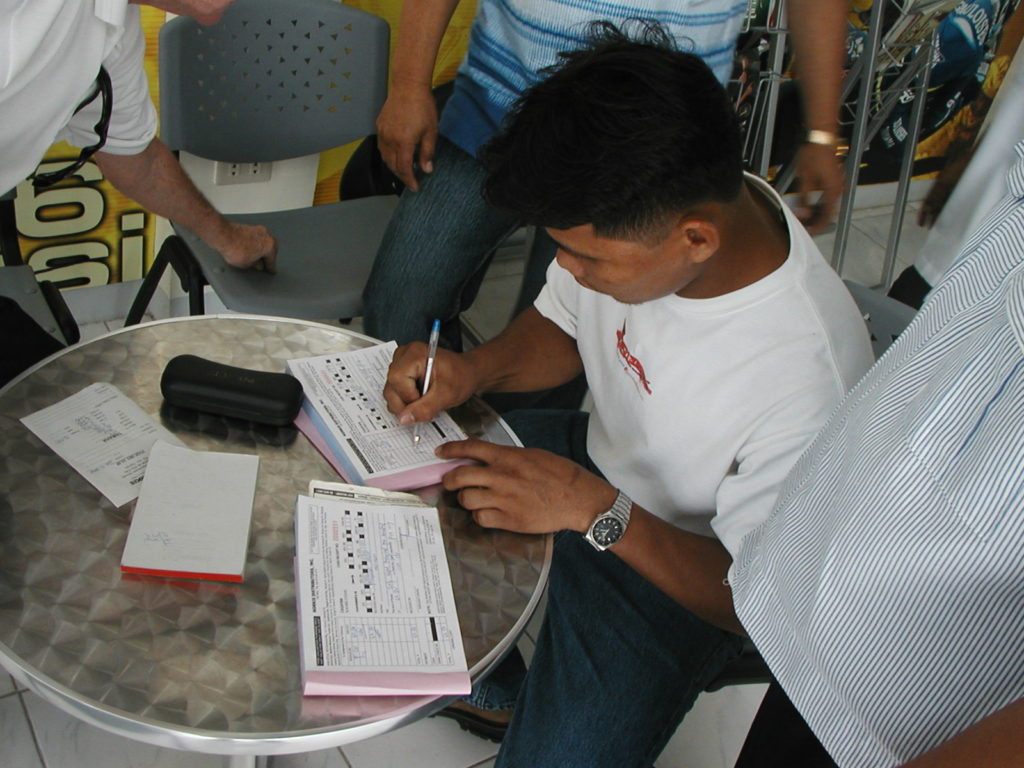

Felisilda signs his name to begin his new life as a tricycle driver in Cagayan de Oro City, Mindanao

“Sometimes he even loses,” Lazarito said. “He doesn’t even make his money back. So I have to pay(the boundary.) But what I’m after is that he learns to make a living.” Sensing an opportunity to help Felisilda help himself, Lazarito got back in touch with the OPBF’s Quill and told him about Felisilda’s new line of work. Maybe, Lazarito queried, the OPBF could just buy Alvin a tricycle and give him a means of livelihood.

Quill readily agreed. Although the regional organization barely keeps afloat, Quill cobbled together some money and wired it to McTavish in the Philippines. McTavish withdrew the remaining funds from Felisilda’s trust account and all together, it was enough to cover the $2000 bill for the brand new tricycle. It is easily the most expensive item Felisilda or anyone from his family has ever owned.

“For a guy from his background, this is like a dream come true,” said Salven Lagumbay, a Filipino boxing writer who flew in to witness the turnover. “If it had been another manager with no connections in Japan, there would have been no replacement with a graft. If this had been Indonesia, Thailand or the Philippines, Alvin might be dead.”

After quietly affixing his signature on the title, Felisilda posed for pictures with Lazarito and McTavish, and then the entire party drove across town to the metal shop which would build Felisilda’s cab on to his new motorcycle.(with the letters OPBF painted on the back, of course.) Within one month, with the guidance of Lazarito, of course, he would be out on the streets running his own business and earning a living.

When asked how he felt about his new business, and if he had any regrets that boxing didn’t turn out the way he had hoped, Felisilda responded with a quote that would make any Chinese philosopher nod their head in approval. For here was a poor and simple young man who obviously realized the value of both the gift of life and livelihood.

“I’m overjoyed and thankful to God that I’m normal, that my speech has been restored,” the reserved and humbled Felisilda said. “I appreciate my life more now. I’m very thankful.” The reservation didn’t last long, however.

“Alvin was very shy yesterday,” Lazarito said the following day. “But when we get back to my house, he shouted ‘I can’t believe I have a new tricycle!’ and he leaped into my arms. He was very happy.”

Ted Lerner is a freelance journalist and author of the timeless classic book, Hey, Joe—A Slice of the City, an American in Manila, as well as a book of Asian travel essays, The Traveler and the Gate Checkers–Sex, Death, Life, On The Road In Asia. Both books are available on Amazon.