How Lionel Rose’s Most Prized Possession Saved The Life Of A Young Boy

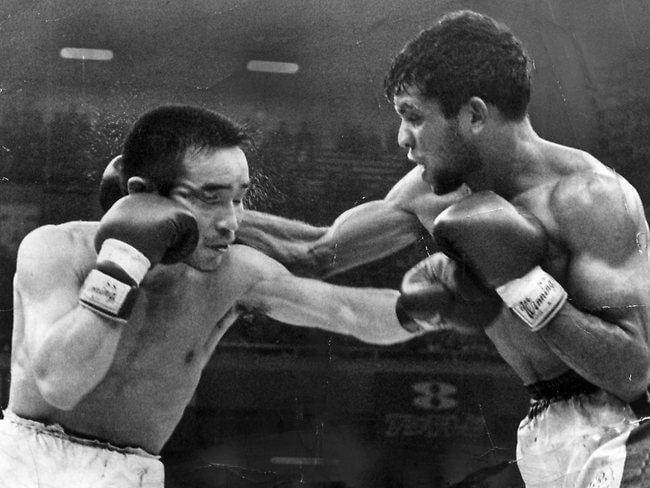

Lionel Rose, right, battles Japan’s Fighting Harada in Tokyo in 1968. Rose defeated Harada by decision after 15 grueling rounds to win the WBC Batamweight world championship. He became the first Aboriginal boxer to win a world boxing title and became a national hero in Australia.

*This article originally appeared in the Ring Magazine and is reprinted here for portfolio purposes only.

By Ted Lerner

Lionel Rose never worried about material possessions. When he won the world bantamweight title in 1968, after a shocking 15 round unanimous decision over the legendary Fighting Harada in Japan, he became Australia’s biggest sporting hero ever and a very rich man. But for this aboriginal Australian, the money and toys mattered little. He preferred to live the way of his people. You live for today. What money you do have you enjoy and you spend on your family, which in the extended structure of Australia’s indigenous people, can number in the hundreds.

Lionel Rose did have one material possession, though, that truly meant anything to him, that he swore he would never let go of; his world title belt.

“Aboriginals are not material,” said Rose’s wife Jenny recently in Thailand, where they were guests of the WBC at their annual convention. “We’re very family oriented. But that belt is important.”

“That’s what a fighter strives for,” said Rose. “That’s a treasure.” Funny, but he had to wait 14 years to get the actual belt. When he took Harada’s title there was no belt available at ringside. So in 1982, the WBC corrected the wrong and awarded Rose a belt, in lieu of the one he never received.

But thirteen years later Rose did what he thought he would never do; he willingly parted with his most treasured material possession, in a magnanimous gesture of generosity that perhaps helped save the life of a young boy.

It was 1995 and Rose had been visiting a friend, a fellow aborigine, in Northern Australia when a call came. His friend’s six year old son, Jandamurra O’Shane, had been playing in the schoolyard when a man, recently released from a mental hospital, rushed in to the yard and poured gasoline over the boy’s head and body and set him on fire. The boy was horribly burned over much of his body, he was unconscious and on the verge of dying.

Rose knew the boy and knew that Jandamurra, like all aborigine kids, revered the man they all called their “Uncle Lionel.”

“Jandamurra was like all the indigenous kids,” Rose said. “He’d brag to all the other children, ‘my uncle Lionel is a champion. He’s a hero.’” Crushed by the young boy’s sudden and terrible fate, Rose felt driven to do something. He immediately called up his wife in Melbourne and told her to retrieve his WBC championship belt, put it in a box and mail it to the hospital where Jandamurra lay fighting for his life. The nurses were to put the belt on top of the boy’s bed so he would see it if and when he woke up.

It was a quiet gesture, done without any fanfare or media coverage. Although the belt meant everything to Rose, he never gave a second thought about giving it to the boy.

“That belt is a spiritual thing to me,” he said. “It’s part of me. I was giving my spirit to him. I think it helped.”

Indeed the boy woke up a month later. He went on to have 27 skin grafts and, while he still has complications, he is getting on with his life. When he got better, Jandamurra offered to give the belt back, but Rose said no.

These were values learned at the heels of his father and mother and a large extended family that numbered in the hundreds. Rose was born in 1948, at a time when Australia’s aborigines were not even classified as citizens. He was the eldest of 12 children, 6 boys and 6 girls. The family lived in a one room hut made of tree bark with no electricity in the far flung aborigine community of Jackson’s Track, which consisted of 100 families, all of them related and all of them dirt poor.

His father worked as an axman(tree cutter) and would often take young Lionel out to shoot rabbits and kangaroos. His father’s tribe, the Goontigamarra, was a known tribe of fighters and warriors. Indeed Rose’s relatives used to work as tent fighters in traveling carnivals, where they would take on local people right out of the audience.

“We didn’t know we were poor,” said Rose. “We were happy.” It wasn’t until he was ten years old, when the family was moved ten kilometers to the nearest city as part of the white Australian government’s assimilation program, that Rose began to understand his people’s predicament.

“I didn’t know discrimination until I met the white man,” he said. “That’s how I learned to fight.” He and his brother were the only two aborigines in a school of 150 whites. “After a week we fixed ‘em up,” Rose says laughing. “They started it, we finished it.”

At 14 years old he found his way to the Warguoo Youth Club, where the manager and trainer of the club, Frank Oakes, already had a small stable of six fighters, all of them white. Oakes immediately took a liking to Rose.

“He took me under his wing,” Rose said. “I stayed at his house every weekend. He was an absolute gentleman.” It was a life changing meeting in more ways than one; this is where Rose first met Oakes’ daughter, Jenny, whom would later become his wife.

He dropped out of school and made boxing his life, finding inspiration in two aboriginal ring legends; lightweight George Bracken and middleweight Dave Sands.

He had his first amateur fight a year later and lost, but won 18 straight over the next two years. When he turned pro in 1964, Oakes introduced Rose to Jack Rennie, who at the time was one of Australia’s biggest trainers and managers. Rose moved to Melbourne and in to Rennie’s house.

“He taught me to get up at six and to be in bed by 8,” he said of Rennie, with whom he’s still close to this day.

“Lionel had natural ability and a willingness to learn and train hard,” Rennie said.

Rennie’s connections in boxing helped put Rose on Australia’s biggest fight cards.

“Lionel’s ability and skills quickly earned him a big following,” Rennie said. “Aboriginal boxers are the underdogs and the white public supports them more so than the white boxers. Generally the aboriginals have quick reflexes, they’re hard punchers, they’re brave and tough.”

It was a potent mixture that made Rose a main event fighter almost from the beginning, drawing packed houses whenever he fought, usually every two months for four straight years. Then in 1968 he got a lucky break.

Jesus Pimentel, the #1 ranked bantamweight from Mexico, was scheduled to fight the Japanese champion, Fighting Harada. When Pimentel broke his hand in training, Harada’s handlers skipped over the next three challengers, also Mexicans, and went right to the nobody Australian ranked number 5.

“They picked the Aussie because they thought he’d be easy,” Rose says smiling. “They got the shock of their lives.” Rose was a 10-1 underdog but the odds clearly seemed much longer. The trip to Tokyo was long and the snow and bitter cold was something he had never before experienced. He was not only facing a bonafide ring legend in Harada, but also 17,000 partisans packed into Tokyo’s Bukidnon stadium as well as three Japanese judges who would have nothing to gain by seeing Rose claim the belt. Nobody expected Rose to win, which no doubt accounts for why only seven people saw him off at the airport in Australia.

Although Harada had struggled to make weight, he came out in his typical whirlwind fashion. The two went toe to toe for 15 rounds and produced a classic war that is still remembered until this day.

“The Harada fight was a hard one from start to finish,” said Rennie. “Harada’s style was to attack from the start and never let up. For 15 rounds Lionel had to fight all the way. His fitness and boxing skills won him the decision.” When it was announced that Rose had won a close unanimous decision, the Japanese fans clapped. By laying it all on the line and beating the legend, Rose became one himself in Japan.

Rose had become not only the first aboriginal world champion, but the first Australian world champion in any sport. The feat proved monumental in a sports loving country like Australia. When he returned to Melbourne a few days later, over a quarter of a million people turned out to greet him, lining the streets from the airport to the city.

“When I saw the crowds at the airport, I first thought that there must be a rock star on the plane.” But then he realized the crowds were there for him. “I was on top of the world. I was overcome. I cried. I came from boiled lollies(a cheap candy) to gold chocolate. It was a bit hard to handle.”

He did a pretty good job of handling his ring duties for the next year and a half, fighting seven times and establishing a reputation on three continents as a tough and thrilling fighter.

After a defense in Japan, Rose got an offer from Los Angeles promoter George Parnassus, who was known for making fights between Mexicans and Americans. He wanted Rose because he wanted the bantamweight title. Rennie was worried about getting cheated.

“I was warned not to take him to America,” Rennie said. “I told Parnassus of this worry and he promoted Lionel in a non title fight with Jose Medal, a hard punching Mexican.” Rose won easily on a unanimous decision.

Parnassus then matched Rose with Mexican number one challenger ChuCho Castillo in the Forum. The fight was a toe to toe classic with Rose winning by split decision. The Mexican crowd went ballistic.

“The Mexicans were a hostile crowd,” said Rennie. “When Lionel got the decision, they rioted and set fire to the Forum and threw bottles at us. We couldn’t leave the Forum until the early hours of the next day.” Parnassus eventually got the bantamweight belt when Rose lost the title in August of 1969 via a fifth round TKO to Rueben Olivares.

“He was better than I was,” said Rose of Olivares. “He was probably the greatest fighter I’ve ever seen.” In all Rose fought five times in the States, two title and three non title bouts. His year and a half of boxing in LA left a big impression.

“He was liked in the States for his boxing style,” Rennie said, “which was a mixture of boxing and fighting. He never shirked an issue and always gave good value for money.”

“He was a passionate fighter,” said WBC president Jose Sulaiman, who saw several of Rose’s fights at the Forum. “He never ran away. Everyone of his fights was a thrill. He fought three superheroes of Mexico and defeated two of them.”

Rose made the move up to Jr. Lightweight and fought for the title in 1971, which he lost by split decision. By then he had been fighting every two months for seven years and was burned out. In 1971 at the age of 23 he retired. He made a short lived comeback in 1975 and retired for good in 1976.

Outside the ring Rose’s new found fame and fortune brought him a life he never dreamed of, and he lived it like there was no tomorrow. He put out several records, two of which went gold. He drove race cars. He made a fortune and spent it on whatever he pleased. He bought several businesses, then sold them after a few years. He traveled around giving speeches and signing autographs. When he was in Los Angeles, he met Elvis Presley when Elvis called him up and invited him over to the closed set of one of his movies. There were books written about him, and even several television mini-series were produced. He was the first ever aborigine selected as a Member of the British Empire and the first ever aborigine voted Australian of the Year.

Rose says he made over $1 million in the short time he was champ, but admits now that most of it is long gone. He has no regrets.

“I spent all my money,” he said smiling. “I enjoyed it. You’ve got to enjoy yourself.” He gave much of his money to his extended family, which in aborigine culture often means hundreds of people.

“He paid for all the aboriginal funerals in his area,” said journalist and OPBF president Frank Quill, a long time friend of Rose. “Lionel would give you the shoes off his feet.”

After his fighting days the good life eventually caught up with Rose. Like some other fellow aborigines he had problems with alcohol and he ran afoul of the law several times. He suffered the ridicule of some sectors but he remained a hero to a mostly understanding public.

“He’s very easy going,” said his wife Jenny who works as a school teacher. “Nothing worries him.”

Lionel Rose, former world bantamweight champion, is honored with a larger-than-life bronze statue at his hometown and birthplace Warragul, Austraila in 2010, one year before he died.

Rose eventually turned his life around. These days he lives modestly with Jenny in an apartment in Melbourne. He works as a volunteer for the Aborigine Sports Commission, giving speeches to indigenous youths. He is still in big demand to appear at functions and his life story appears in all sports history books and magazines.

It was several years ago when Quill, who happens to also be the WBC ratings committee chairman, received a request from one such local magazine which wanted to do a story on Rose. The magazine specifically wanted to take Rose’s picture with his WBC belt. When Rose told Quill that he no longer had the belt and that it was now with Jandamurra, Quill knew something had to be done.

“I got in touch with Jose Sulaiman and I told him the story,” Quill said. “He agreed to give Lionel a new belt.” The WBC and the OPBF paid for Rose and his wife Jenny’s airfare and hotel bill for the WBC’s annual convention in Pattaya, Thailand this past December. Quill informed Jenny what was in store, but kept it a secret from Rose.

At a packed banquet at Pattaya’s Ambassador City hotel, Rose’s selfless deed for a young boy in need was recognized and honored by the international boxing community, which gifted him with a brand new WBC title belt. Upon receiving his shining new belt, Rose broke down crying.

“He gave away his most treasured possession,” said Rose’s wife Jenny, shaking her head in disbelief, “then out of the blue he gets another belt. And in front of all these boxing people. He’s a good role model. Aborigines don’t have a lot of role models.”

“I admire him very much,” said Sulaiman. “He’s the perfect representative of an authentic champion. After retirement he went through some sad moments. But he was able to defeat his vices. He was not only a great champion, but a man of nobility.”

“The belt is nothing,” an emotional Rose said afterwards. “I just wanted to help the young fellow.” But, of course, that belt is everything to a champion, as was obvious moments later in the way Lionel Rose tightly clutched the one possession in this world he values the most.

“I’m blessed,” Rose said looking down at his new belt. “This is the icing on the cake.”

*Lionel Rose died in 2011 at the age of 62 and was given a state funeral by the government of Australia.

Ted Lerner is a freelance journalist and author of the timeless classic book, Hey, Joe—A Slice of the City, an American in Manila, as well as a book of Asian travel essays, The Traveler and the Gate Checkers–Sex, Death, Life, On The Road In Asia. Both books are available on Amazon.